I can recollect back to a time when I didn’t get excited about Ramadan. It was when all I could focus on was how many things I would have to give up- sleep, food, drinking stuff; and, then there was the “other stuff” like watching TV, having to sit through khatiras, not being able to just be content with where I am spiritually, because of the constant religious reminders of my inadequacy- all of this meant having to start doing things differently. My life would have to accommodate Ramadan, inevitably Ramadan brought about change that I just was not interested in.

To me these changes were drastic, and even the period of thirty days was too long. I cringe at that old me. Things are acutely different now, as they have been for a several years: three months before, I build up excitement in anticipation; and, when Ramadan ends, I feel like something special ended with it. I imagine that this is the sort of excitement that Yusor, Razan, and Deah would be anticipating Ramadan with. They, however, were killed in their Chapel Hill home by a gun totting white man, who isn’t a terrorist.

For Deah and Razan it would be a time bubbling with excitement, they would be focused on their first Ramadan spent as “Dezan” (they had just become a married couple that winter). The two of them would also be planning for their upcoming trip to Turkey, benefiting Syrian children, made refugees by the brutal Assad. I can imagine them seeing Ramadan as an added benefit to their trip planning, as it is a month filled with Gods blessings and mercy. They would take special care to make extra special supplications on making this trip a benefit for the people they hoped to assist, a successful endeavor and safe for them.

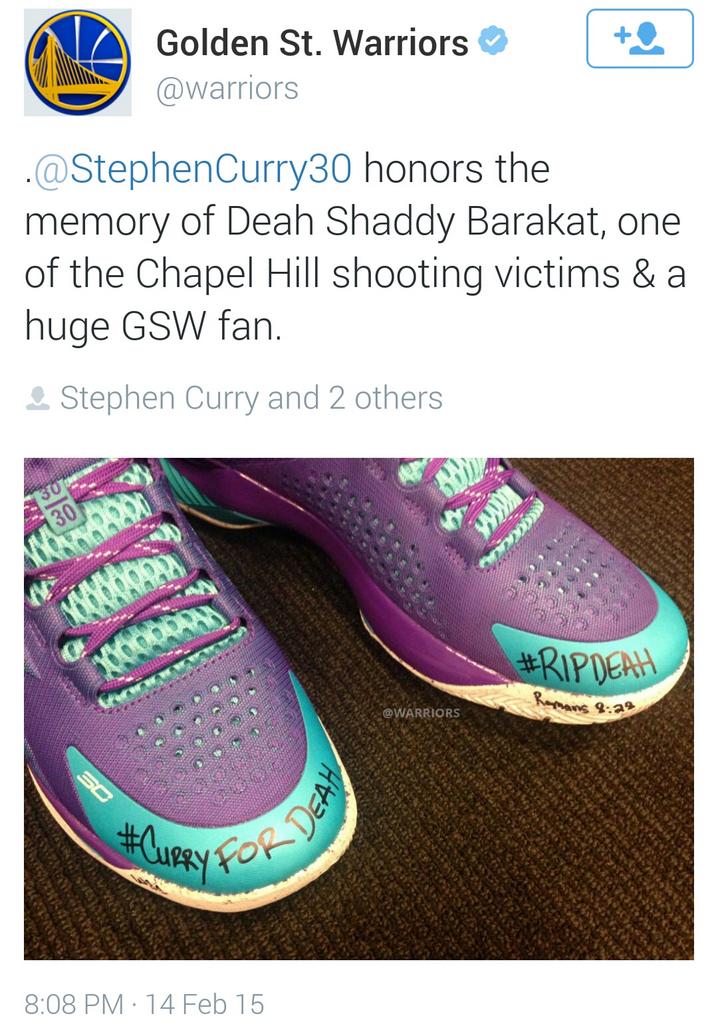

But in the first few days, Deah, well he might be a little distracted with the NBA playoffs. He would be watching with excitement as his favorite player, Curry, took his team head-to-head against Lebron James, and won. Deah, called it a year ago.

I didn’t know Yusor, no more then I knew Deah or Razan, but I can tell you about her excitement for Ramadan. She was training for a marathon, so she probably would be laser focused on finished that up and cruising into Ramadan. And she cared about education. I shared her NPR StoryCorps sentiment about education- access to education and leadership development is something that intertwines my own sense of community service and responsibility to my community.

I can say this with a certain degree of certainty because in Deah, Razan, and Yusor, I see myself and my friends and the people I care for. They were Muslims, making their place and their contribution to America. They were an ideal of what an American Muslim identity might manifest itself to be. Their death was violent, random, and still unexplainable, worse the response by folks outside the community, both private and public institutions, was lacking and disrespectful.

But, The Reality…

Deah, Razan, and Yusor could “pass” for being white Americans. The only differentiating aspect for them would be their names. If they chose to, they could fully pass themselves off as being white. Yet they found that no qualms practicing Islam and being American. They melded their identities into one. However, what if they chose to reject their American identity and wrap themselves in a cultural enclave mentality? What would my response have been? Would it have become such a big issue? Or what if they chose not to be “orthodox” Muslim, would there be such a outcry?

I am wracked with these questions, seemingly existential in nature, because so much has happened since their deaths. From Black churches burning to Black lives being taken, we are rudely and violently reminded about the racial underpinnings of minorities in America. We have principles and values that are high in their call on human conscious, yet social constructs and ills that undermine those precepts. Its very precarious nature seems self evident in how institutions focus on a CVS burning versus ten Black Churches being burned in a span of three weeks. #WhoIsBurningBlackChurches?

Even if I set aside the existential probing, the fact that there was enough hatred and violence for a person to execute them for their race and/or religion, whether it be Charleston, South Carolina or Chapel Hill, North Carolina, can’t be ignored. I can’t just shake my head and sigh.

As a Muslim, Chapel Hill personalizes the pain and fear and anxiety of communities that are targeted or mistaken to be Muslim, in particular the Sikh community. From Charleston to Chapel Hill, the inextricable thread is that Oak Creek happened, and we shook our head (even some sighing that it wasn’t really Muslims…really?!?). The response to which was drastically different, yet evident of the priorities placed on one communities pain and suffering. In neither cases were these white males considered terrorists, lone wolves, in need of government intervention programs to counter violent extremism.

But the message these white males wanted to send is that Muslims are not welcome, and that all Muslims are suspect, even if you are perceived to be Muslim; and worse, they have no access to the justice system or to human decency. It was a message all to clearly reinforced by the Phoenix Biker Rally in Arizona. Just as there are suicide bombers willing to blow themselves up for a perversion of Islam, there are white males who have enough reservoir of hate to indiscriminately kill, or intimidate a community with loaded guns, for it. They are both forms of terrorism, yet only one is recognized by the Federal government as such.

I think that when I delve deeper into Chapel Hill and my psyche, I get a sense of the trauma that one has living in constant fear. You don’t know when some white person with a gun will feel the need to take out their anger over a parking spot because you happen to be the Muslim in that spot. It seems irrational, but how do you rationalize an irrational fear? I feel like this is how it feels to be a person living in rural Pakistan or Yemen (before the Saudi assault) with American drones flying over, or living in Afghanistan or Iraqi cities or in the urban sprawls of Pakistan’s megalopolis Karachi with lunatics ready to bomb mosques and funeral processions, or for that matter, how it feels to be an Israeli on a bus or at a restaurant. Its unnerving, even if you accept that death is the ultimate human condition.

So there is community, or lack there of…

Deah, Razan, and Yusor were part of a tight knit community. I heard of their murders from a North Carolina Imam, Sheikh Faqih of the Islamic Institute of Orange County, who saw the three of them grow up, while he ministered to the community out there. This community, while in the millions is large and world events are felt within the community, as are domestic ones. In Ramadan, you feel things intensified, as domestic and world events converge and resonate in local communities huddling together to break fast and offer prayers.

Deah, Razan, and Yusor were part of a tight knit community. I heard of their murders from a North Carolina Imam, Sheikh Faqih of the Islamic Institute of Orange County, who saw the three of them grow up, while he ministered to the community out there. This community, while in the millions is large and world events are felt within the community, as are domestic ones. In Ramadan, you feel things intensified, as domestic and world events converge and resonate in local communities huddling together to break fast and offer prayers.Ramadan is a time for intense communal prayers, so the feelings are already heightened. Community is what you turn to in times of trauma and in times of joy. Community affects how one responds to these moments in life. In its essence community is a group of people bounded together by shared sense of belonging and feeling of identity. But just because one is a Muslim doesn’t mean that every community is welcoming and sensitive to everyone. There is an orthodoxy, there is a prioritization, whether conscious or unconscious.

For many years now, I was becoming a satellite Muslim. I used to be attached to specific mosques as I moved around Southern California. But in recent years, I had allowed the distance between me and the Mosque to grow. I didn’t see that there was anything wrong with having a long distance relationship. I would attend prayers when I needed to, I would go to Friday sermons, but I had no desire to invest in any particular Mosque community. I was detached, and I had been developing my own sense of spirituality without the need of the Mosque, or any organization, facilitating it for me.

There was a time once, where I was fixated on one Mosque. It encapsulated the essence of community for me. Things happened, and I drifted, looking around for the next space, the next sense of community. But I never “anchored” anywhere. I felt most vulnerable about not being “anchored” during the days and weeks following Chapel Hill murders. I learned during this time the need for a safe space.

I didn’t find that “safe space” in the mosque. Instead of blaming the mosque community, I turned internally for the problem and refused to place the onus of responsibility on the external actors: the Mosque was good, I was looking for things in all the wrong places, is how rationalized my feelings.

This idea of what the Mosque is or isn’t, actually is something I have I grappled with for the past seven years. The conclusion I drew from this internal dialogue was that the mosque should provide prayer space and Friday sermons. Everything I wanted, it might not be the responsibility of the mosque. But I realize my internal dialogue, is a shared Millennial American Muslim issue. Like so many in my generation, we are grappling with the fact that the Mosque does not reflect our sense of self or community. What that might be is a whole other blog reflection.

The Virtual Ummah and the Need for a Radical American Muslim Identity

The Millennial American Muslim dilemma is expressed in the way that the response to Chapel Hill developed over the course of the hours and weeks that followed. People didn’t turn to their mosques or institutions, but rather the virtual space became the tool to process everything. It wasn’t two weeks after the events of Chapel Hill did some mention of it actually make its public appearance in a Friday Sermon at my Mosque. Sadly it was lacking in many dimensions, and further turned me off from the Mosque being a “safe space.”

But the online community, it was facilitated by Farris Barakat, Deah’s brother, who set up a Facebook page commemorating Deah, Razan, and Yusor immediately after the murders. He, informed by his Millennial experience, took it a step further, branding the legacy of the three with a slogan- “Our Three Winners”- along with a iconographic sillouhete based on a graduation photograph of the three students. This striking graphic along with the rallying slogan facilitated the creation of an online space.

From hashtag campaigns to posters adorned with silhouettes of the image. Anger at the lack of media attention and the lack of police response was channeled through social media streams. This was driven by a Millennial sensibility, there was no Mosque and no organization that pushed this campaign forward. It was an amorphous reality, coming into existence out of a collective cyber shock and grief, driven by hundreds of thousands of individuals. It was a virtual space, and it took the community a couple weeks to catch up to the sentiment.

There are many social media marketing and strategy principles that we can draw out and create successful case strategies of, however, for me the principle reality is that it was a departure from the institutional Muslim response and an assertion of a radical American Muslim collective identity. It was one removed from institutional powers, and based on self empowerment.

This identity refused to let leaders take the rein and push a narrative, but rather through hashtags and social media, deluge and sway the national discourse around the issue. Out of this new leaders emerged, principally the family members of the three murdered Muslim students. There voices were unapologetic, loud and unwavering.

It’s a Funny Thing, Vicarious Trauma

I didn’t know what vicarious trauma was until a friend sent me a link to a survey about it. The survey didn’t help explain the concept, google did. But I realize now that I had stepped into a world where I was potentially suffering from vicarious trauma, because I need something to explain away what happened to me. I am trying to rationalize this whole thing. I wanted to withdraw, I lost sense of hope, I felt vulnerable, I had no desire to think about a future, my soul felt violated- why? How could an event three thousand miles away, happening to strangers affect me so drastically?

It wasn’t so much that I lacked a physical space where I could share and be with others to express my grief and sorrow, or that the online space was not empowering. The fact was that I had experienced years of working with people who were experiencing traumatizing experiences- bullying, hate crimes, religious discrimination in the work place. But I had created a buffer and a means of dealing with those intense emotions. Four years on, I became a civilian again, and Chapel Hill touched on feelings and emotions long dormant and shut away.

What is interesting is that I feel that even further down the rabbit hole, Chapel Hill sent home a message that there was no longer an American Dream for Muslims. Its hard for me to fully dissect it, but what I felt was that no matter how hard we Muslims try to buy into this American reality of ours there are those who clearly are willing to kill in order realize their narrow limited definition of America. In that context, I see this as a battle between two very confrontational versions of what Americas future will look like. On the one hand is Deah, Razan, and Yusors’ America (as well as mine, and many many others), on the other its Daniel Pipe, Bridget Gabriel an army of bigots and haters, which includes “white terrorism.”

In the face of #BlackLivesMatter and all the resulting realities of this, it feels like I stand on the precipice of constant anger, utter disappear, naked vulnerability every time I hear about innocent lives being taken and the media circus that ensues to wallpaper over white terrorism and institutional abuse of power.

Having constant communication and access to the world, its a sort of anguish in the disguise of a blessing. It requires now that we consciously “disconnect” ourselves, that we be intentional in our experiences of real time interactions. We have to self-regulate and police our access and response to emails. We have to give warnings about “triggers” or that it might be to “graphic” or “not safe for work.” Through it all we repeatedly put ourselves at risk of suffering from a thousand cuts not realizing how much blood we’ve given up- sacrificed- to stay connected. This is life lived in trauma. Interestingly enough, this is the sort of “connection” God provides for us during Ramadan. The irony being that there is no digital line to God.

Maybe we should have a warning that overexposure to news might not be good for your soul. While last Ramadan was punctuated by Israeli military rape of Gaza, this year, well, this year, I’ve tried to internalize and be selfish, and in Chapel Hill, it must be a solemn affair because how else do you respond to being left without loved ones?

So its not so much that I will accommodate Ramadan, its more that Ramadan accommodates for the human condition. I think I needed it more then ever this year. It removes the grief and the sorrow and allows a believer to escape and be enveloped by God. I have the luxury to be free of violence and war, hunger and poverty, but also the responsibility of keeping folks in my prayers and thoughts. Its a fine balancing act, to not fall over the precipice. And maybe thats the privilege?

Leave a Reply